Uncategorized

PAPSS and the Paradox of Africa’s Payment Revolution

By Fava Herb

When the Pan-African Payment and Settlement System (PAPSS) was launched in January 2022, it was billed as a quiet revolution in Africa’s financial architecture. By allowing cross-border payments to be settled in local African currencies—without routing transactions through the dollar- or euro-dominated correspondent banking system—PAPSS promised to remove one of the most persistent bottlenecks to intra-African trade.

Three years on, the system’s potential is widely acknowledged. Its adoption, however, has been markedly slower than its architects had hoped.

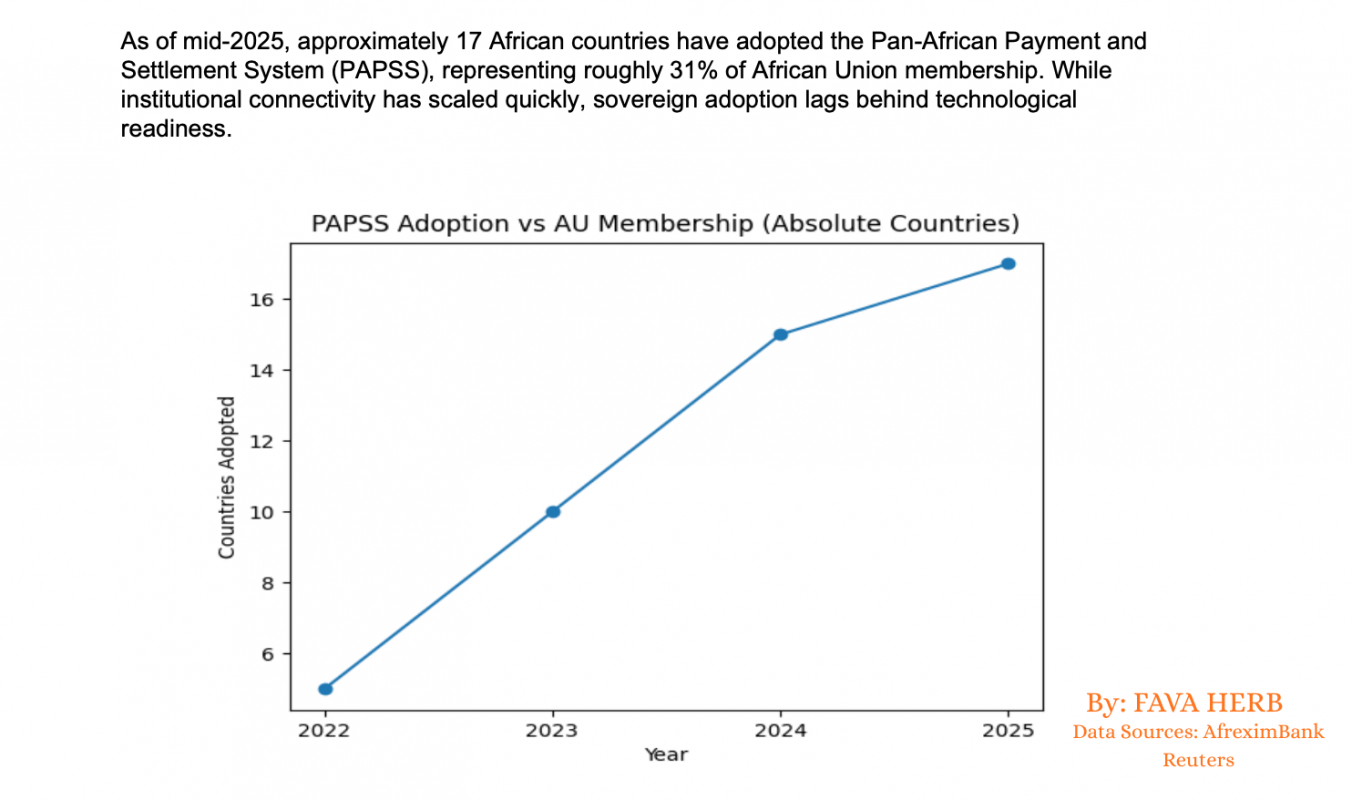

As of 2024–2025, only about 17 African countries have formally joined PAPSS, out of 54 African Union member states—roughly one-third of the continent. This uneven uptake highlights a broader paradox: Africa has built a credible, home-grown payments infrastructure, yet political, regulatory and monetary fragmentation continues to limit its reach.

A System Designed to Fix a Structural Flaw

Africa’s payments problem is well documented. According to Afreximbank, over 80% of intra-African trade payments have historically been routed through correspondent banks outside the continent, even when goods never leave Africa. This structure raises transaction costs, exposes traders to foreign-exchange volatility, and ties African commerce to external liquidity conditions.

PAPSS was designed to change this. Developed by Afreximbank in collaboration with the African Union and the AfCFTA Secretariat, the system enables a buyer in one African country to pay in local currency, while the seller receives funds in theirs. Central banks settle the net positions, eliminating the need for third-currency conversion.

Afreximbank estimates that full continental adoption could save Africa more than US$5bn annually in transaction costs and foreign-exchange leakages—an amount that exceeds the annual GDP of several smaller African economies.

Progress, But at a Measured Pace

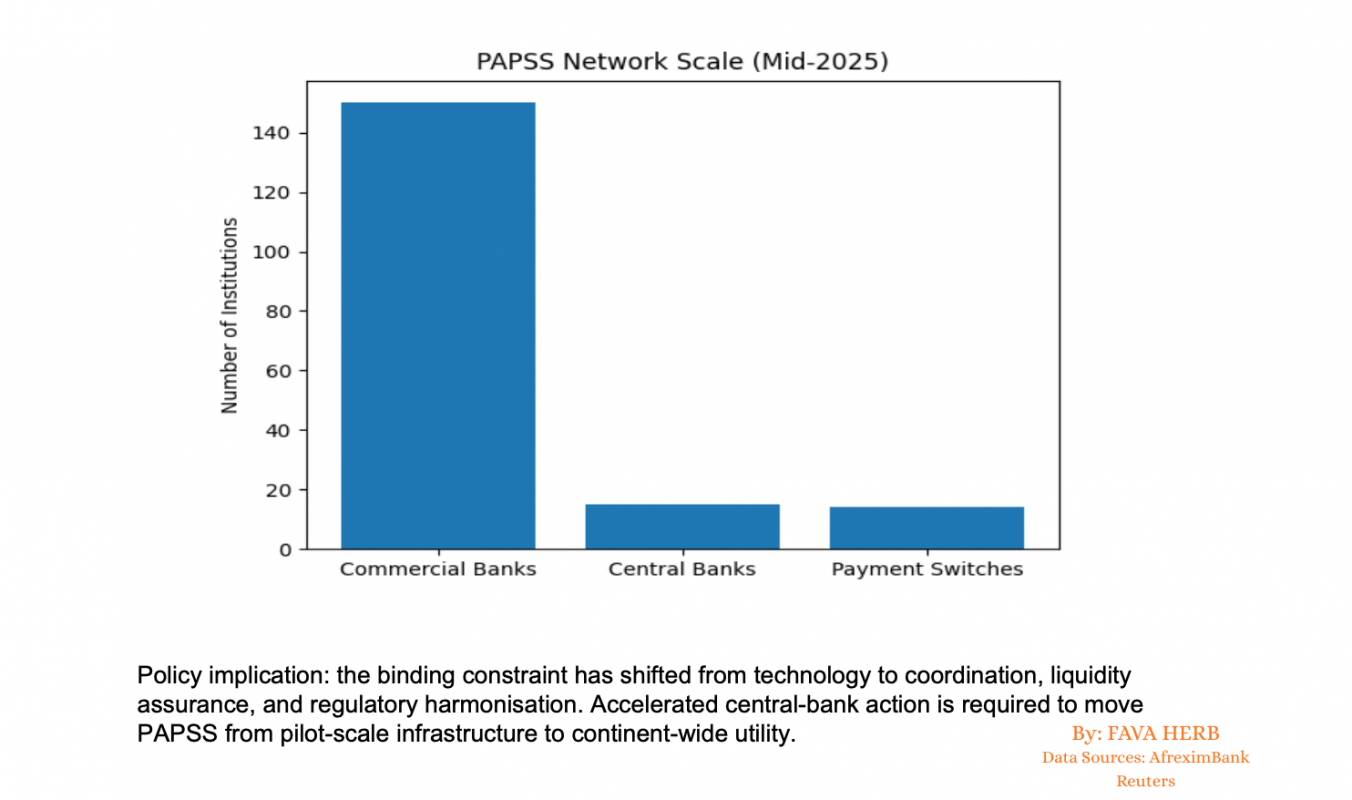

There has been real progress. PAPSS has moved beyond pilot status, onboarding more than 150 commercial banks, several major regional banking groups, and over a dozen central banks. Nigeria and Ghana have emerged as early leaders, while recent additions from East and North Africa signal growing geographic spread.

Yet the headline number remains striking: 17 countries after three years, against a backdrop of political rhetoric that routinely frames AfCFTA as a pan-continental project.

For comparison, the Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) reached near-universal adoption across the EU within a few years of launch—helped by strong supranational enforcement, regulatory harmonisation and a shared currency framework. Africa lacks those institutional advantages.

Why Uptake Has Been Slow

Several factors explain the cautious pace.

First, monetary sovereignty concerns loom large. Some central banks remain wary of exposing domestic payment systems to cross-border settlement mechanisms before capital-account controls, FX liquidity and reserve adequacy are fully aligned.

Second, regulatory fragmentation persists. AML/KYC regimes, data-localisation rules and settlement finality laws vary widely across African jurisdictions, raising compliance costs for banks considering PAPSS integration.

Third, currency risk and liquidity constraints remain unresolved in many corridors. While PAPSS removes the need for dollars, it does not eliminate volatility in thinly traded African currencies. For treasurers and banks, this makes large-value settlement a more complex proposition.

Finally, there is a coordination problem. PAPSS becomes more valuable as more countries join. Until a critical mass is reached, some states prefer to wait rather than move first.

Strategic Stakes for AfCFTA

The slow uptake matters because payments infrastructure is not ancillary to AfCFTA—it is foundational. Intra-African trade still accounts for only 15–18% of Africa’s total trade, compared with around 60% in Europe and over 40% in North America. Without cheap, predictable and fast settlement mechanisms, tariff liberalisation alone will not unlock regional value chains.

This is why PAPSS has increasingly been framed not merely as a banking innovation, but as strategic economic infrastructure. In 2024, the system expanded its ambitions with the launch of the African Currency Marketplace, aimed at improving liquidity between African currencies and reducing dependence on hard-currency intermediaries.

If successful, this could deepen local FX markets and make PAPSS more attractive to risk-averse banks and corporates.

The Road Ahead

PAPSS is unlikely to fail—but neither is it guaranteed to succeed at continental scale. Its future will depend on whether political commitments under AfCFTA translate into binding regulatory alignment, whether central banks are willing to prioritise regional integration over short-term monetary caution, and whether liquidity tools evolve fast enough to manage currency risk.

The lesson from the first three years is sobering but instructive: infrastructure can be built faster than trust.

Africa now has a payments system designed for its own trade. The harder task is persuading more than 50 sovereign states to use it.